ONE YEAR LATER, IS THE NEW OPRA ACTUALLY HIDING CORRUPTION?

The Open Public Records Act isn’t really all that ‘open’ anymore.

In this June’s primary election, almost a year to the day that Governor Phil Murphy signed into law a major revision of the Open Public Records Act (OPRA), making it harder for the public to access government documents and oversee elected officials, Assemblyman Joe Danielsen, the main author and champion of that law, came within 500 votes of losing his seat precisely because of it.

His opponent was Loretta Rivers, a school board member and nonprofit director from Piscataway. Continuously frustrated by her inability to get government documents she needed for her nonprofit advocacy work, she finally had enough, she told The New Jersey Democrat. She launched her campaign with its focus on transparency and the public’s right to know what their elected officials are doing. Unlike her opponent, she and supporters went door to door explaining what OPRA had done to oversight of government. Voters were very receptive, said Rivers, who won 48.9% of the vote against Danielsen, who has held his seat since 2014. In a July 14 op ed in the New Jersey Globe Rivers wrote, “I ran to serve and my race has just begun,” an indication she plans to take Danielsen on again.

The public was solidly against changing OPRA. A Fairleigh Dickinson University poll last year found that more than 81 percent of voters wanted to keep it as is. And virtually every advocacy group and union from the ACLU-NJ, the League of Women Voters, the New Jersey Press Association, Citizen Action, New Jersey Working Families Party, the state AFL-CIO and more than 17 other unions opposed the proposed changes that were clearly aimed at stifling access to information. New Jersey Comptroller Kevin Walsh testified before the legislature that making it harder for the public to access public documents will lead to “more corruption, fraud, waste, and abuse.”

Yet major changes to OPRA passed and they will be the signature accomplishment of the two-year legislative session now ending. So, what impact have the changes to OPRA had?

“We know that the OPRA bill severely limited our access to public records and our ability to hold elected officials accountable in the year since it’s passed,” Jim Sullivan, ACLU-NJ’s interim policy director, told The New Jersey Democrat. “But we don’t know what we don’t know, because the bill limited transparency so much. It's not one single provision that makes the bill particularly bad. It's all the provisions together.”

Sullivan said that the changes in who pays legal costs when a request is denied have had a chilling effect. Under the old rules, if a court challenge over a denied request was successful, the town or agency paid the costs. Lawyers told TNJD that the possibility of these charges caused town clerks to be very careful about what they denied. But now courts have discretion over who pays costs. And lawyers hesitate to take a case on contingency, asking people fighting denials to pay upfront. “There are less avenues for people that are denied OPRA requests to fight them,” Sullivan said. “So, people are either not filing, knowing they are going to have to hire an attorney to get them, or being denied and not taking it any further.”

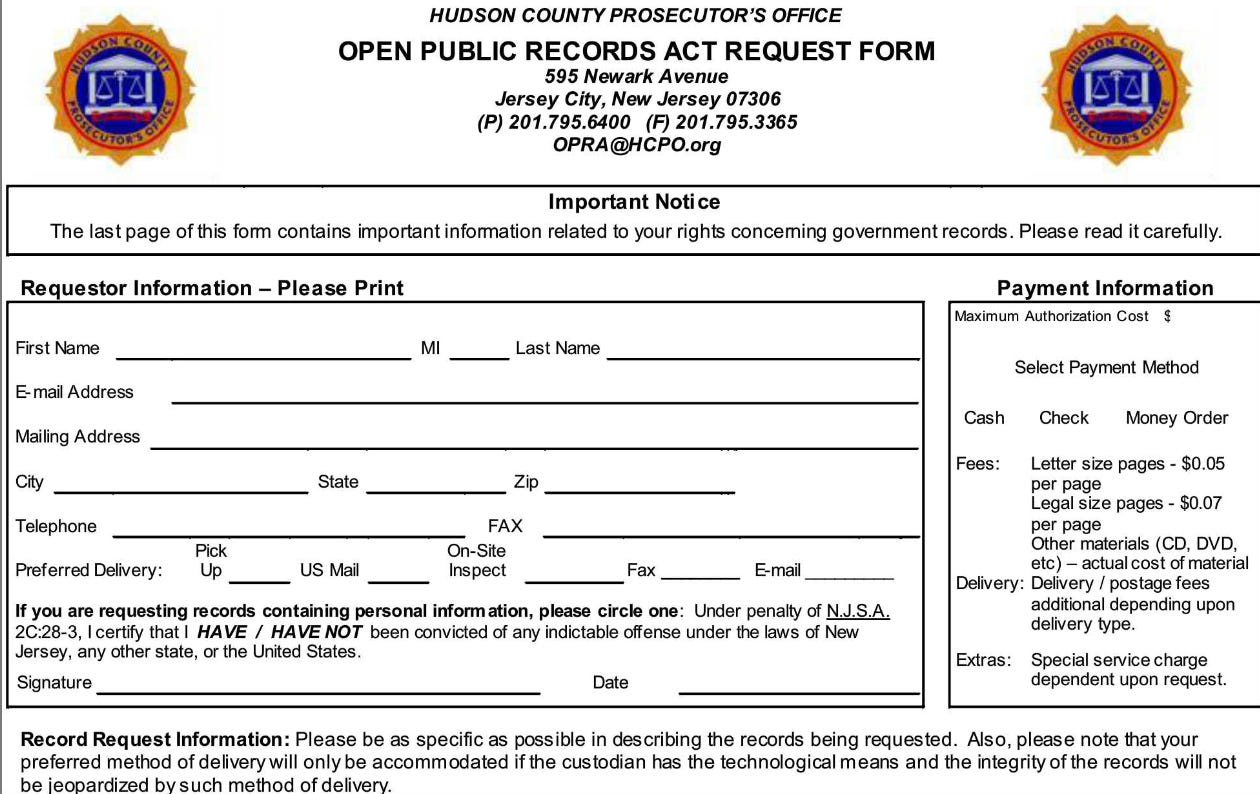

“It codified a lot of hurdles,” just to have an agency respond to you, CJ Griffin, a partner at Pashman Stein Walder Hayden P.C. and director of the Justice Gary S. Stein Public Interest Center, told TNJD. Previously, someone could just email a request to get the town’s budget, but now specific forms have to be filled out. “There are lots of agencies that don’t even have the correct form on their website,” she said.

And once that is done the delays start.

“With the new statutes they can just take extension after extension and so we’re just seeing a lot of delays,” added Griffin. “The delays have always been a problem and they’re an extra problem now because the statute was amended to say they can take extensions.” And, echoing ACLU’s Sullivan, Griffin said that if the requests are denied, the changes in who pays legal costs of challenging denials “makes it very difficult to challenge their actions.”

Griffin has represented reporters and others in hundreds of OPRA cases, many of which significantly expanded access to law enforcement records and videos. Now police departments are using provisions of the new law to reverse that, Griffin said.

Agencies could always impose service charges if it required extraordinary effort to respond to a request, but now, if a requester thinks the fees are unreasonable, they have to prove it. Previously it was up to the entity imposing a fee to prove they were reasonable.

“So, what we’ve seen is that it is being used by police departments to try to keep body cam and dash cam videos from people,” by imposing thousands of dollars in fees, said Griffin, adding it is also being used to keep emails secret. She said:

They’ll just come back and say, ‘Oh there are a thousand emails and so we’re charging a dollar a page and that’s $1,000.’ I’ve seen a lot of it. The agencies know that service charges in particular are difficult to challenge and it’s a way to just get you to go away because most people can’t afford to pay hundreds or thousands of dollars for public records.

Of course, New Jersey has long ranked high in corruption, as TNJD has detailed. Public watchdogs were hopeful when the 2002 OPRA law significantly expanded access to government documents, and media investigations and public monitoring led to the exposure of police misconduct, local bribery scandals, toxic chemical polluters, and the infamous “time for some traffic problems in Fort Lee” story that derailed former governor Chris Christie’s political ambitions.

The League of Municipalities has long sought to clamp down on this access, arguing that people filed numerous frivolous requests costing governments time and money. And companies mined local data, at the public’s expense, to use for commercial or advertising purposes, the league argued.

The league found support from New Jersey’s legislators, many of whom have an intricate relationship to local towns. Some are mayors or municipal officials, others lawyers who provide legal advice or own companies that contract for other services. For example, the law firm of Assembly Speaker Craig Coughlin, who steered the bill through the Assembly, provided legal services to more than three dozen towns last year, reaping millions of dollars, according to their filing with the New Jersey Election Law Enforcement Commission (ELEC).

Loretta Weinberg, the former Senate majority leader, told TNJD she had wanted to reform OPRA, not blow it up. “I worked for at least two years on updating OPRA because it needed it,” she said. “There were legitimate complaints from the clerks’ association, from the League of Municipalities, and we tried to answer all of those that were legitimate. When push came to shove, all the League of Municipalities wanted to do was not correct any excesses in OPRA but to shut it down. And they won the battle.”

Weinberg said she “included them in every step of the way. And every time we solved one problem, they moved the goal post and there was another problem. So, I think they were, in my experience, the main advocate who really didn’t want to solve problems. They used that as a stalling technique, but really wanted to close down OPRA as much as they could.”

She proposed such things as limiting the number of requests an individual could make in a month and putting documents online as the way to handle the League of Municipalities concerns. And she said there was even money for towns that didn’t want to create their own online system to use a state site that would be free. “And the next thing you would hear is they couldn’t put all this online, it takes too much time,” she said. “My experience is the League of Municipalities was not a good partner and they didn’t have the same goals that I and some of my colleagues had.”

In January 2022 Weinberg retired from the legislature and Senate President Steve Sweeney, who let Weinberg lead on this issue, was ousted from the Senate. Senator Paul Sarlo, who also happens to be mayor of Wood-Ridge, replaced her as head of the Senate Budget and Appropriations Committee, and was Senate point person for the bill, along with Senate President Nicholas Scutari, who said he got interested in the issue after speaking at a League conference. In the Assembly, Danielsen and Coughlin led the effort.

There was cajoling and back room deals and offers related to the budget, gasoline taxes and affordable housing, according to a comprehensive article by Brent Johnson at NJ.com, who wrote that at one point Scutari even threatened not to hold a vote on a school funding measure, unless OPRA passed. One Assembly member who voted for the OPRA changes told TNJD, “I was doing what I thought was the best outcome for my district. They can take things away from you or don’t award it.”

After contentious hearings when numerous organizations and unions spoke out against the measure, Coughlin pulled it for further discussions and made some concessions to the unions. Ironically the limited restrictions in the bill on data mining, a key League of Municipalities complaint, were removed from its final version. And Griffin says that although the law encouraged agencies to put more records online “I’ve seen no evidence of that happening at all.”