Why are so many building trades unions supporting Steve Sweeney for governor?

It’s all about the machine. Here’s how it works: South Jersey boss George Norcross, who’s now under indictment for running a “criminal enterprise,” controls an enormous political machine that includes a corrupt patronage system that doles out lucrative contracts to real estate developers and construction contractors. Those developers and contractors have long forged an alliance with the building trades unions, who work together not only on, say, roads and bridges, but on politics, too. And Sweeney, the long-serving former state senate president, has always been a cog in that machine, greasing the wheels for Norcross, the developers and the building trades unions.

That’s how it works all over New Jersey – but in Camden, the home field of Norcross and Sweeney, in particular.

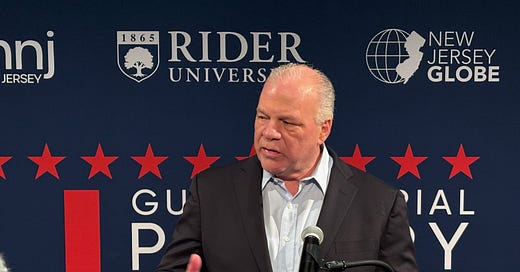

Steve Sweeney’s gubernatorial campaign pitch is that he is a fighter for workers, someone who as state senate president pushed through a generous minimum wage law and a paid family leave benefit, all of which makes him labor’s candidate. He’s won the endorsement of the carpenters, roofers, electrical workers, sheet metal workers, boilermakers, bricklayers, the International Association of Bridge, Structural, Ornamental and Reinforcing Iron Workers, the South Jersey Building Trades and Construction Council and Bill Mullen, president of the New Jersey State Building & Construction Trades Council.

Yet he has been booed off the stage at town halls by public sector union workers furious at his continuous attacks over the years on their pensions, benefits and wages. The leading teachers’ union spent millions of dollars in 2017 trying to throw him out of office. And none of these unions are backing him in his current run for governor. Nor are progressive health care unions such as SEIU 1199 or SEIU 32bj.

That’s largely because, from his powerful perch as state senate president, Sweeney time and again has targeted public sector workers while allying with the building trades when it comes to how to spend tax dollars. For all these unions, public money is important, but in different ways. For public sector workers, teachers, firemen, police, and others, it means salaries, pensions and benefits. For the construction unions it means public works projects, roads, and new buildings that provide them jobs.

The building trades members and the public sector workers “are looking for different things, their motivations are different,” Micah Rasmussen, director of the Rebovich Institute for New Jersey Politics at Rider University, told The New Jersey Democrat. “Trade unions are trying to generate work for their members, even when that means tax dollars for public works. Public employee unions are looking for job protection.”

The split in the labor movement goes back to the 1930s and the development of unions based on a specific trade and those based on a specific industry, says Susan Schurman, professor of labor studies and employment relations at Rutgers. “In the recent past it’s been the business unions vs. the social unions.” While the business unions are concerned with their own job issues, wages, and contracts, the social unions “view themselves as advancing the welfare of workers in general and not just the dues paying members.”

To put that in its starkest terms, the building trades unions, who often earn high wages, are pretty much looking out for themselves. Other unions, representing public sector, health care, and other nontrade workers, often paid much less, often support broader issues affecting all their members such as health care coverage and housing.

When Governor Murphy asked for a millionaires’ tax to help close a budget gap, Sweeney was opposed. “Demonstrators, mostly members of the Communication Workers of America, which represents public workers, turned out en masse to try to head off cuts to pension and health care benefits proposed by Senate President Steve Sweeney,” according to one news report in 2019, on Murphy’s plan to raise taxes on New Jerseyans earning more than $1 million a year. “So far, the union's efforts seem to have left Sweeney unmoved.”

Though union-connected himself – a former iron worker, his father was president of a large South Jersey ironworkers local now run by his brother, and he is the vice president of the New Jersey branch of the International Association of Bridge, Structural, Ornamental and Reinforcing Iron Workers – one of his first acts when elected to the state senate in 2006 was to demand a 15 percent salary cut to state workers rather than increasing the state sales tax as proposed by then-Governor Corzine.

Public sector ire against Sweeney reached a peak in 2011 when he rounded up enough Democratic votes from the Norcross political machine, as well as the Essex County machine of Joseph DiVincenzo, to pass Chris Christie’s bill requiring that state and local government workers, including teachers, police and firefighters, pay thousands of dollars more for their pensions and health insurance. And over the ensuing years Sweeney reneged on promises to enact a guarantee of full state funding for their pensions.

The NJEA spent $5 million on ads trying to unseat Sweeney in 2017. Opposing the teachers’ union were PACs affiliated with Norcross, including his General Majority PAC, that spent millions targeting Sweeney’s opponent. Its treasurer at the time was Tricia Mueller. She was also treasurer of the electoral arm of the Northeast Regional Council of Carpenters, which was funneling hundreds of thousands of dollars into Norcross’s PAC.

Sweeney’s ties to the Norcross political machine have meant lucrative construction contracts for the building trades in a number of ways. Legislation that Sweeney, as senate president, was critical in enacting in 2013, opened the door to some $1.6 billion in tax breaks for companies agreeing to invest in Camden. And, as ProPublica detailed, $1.1 billion of that went to Norcross’s own insurance brokerage, his business partners, and clients of his brother’s lobbying and law firm. (That’s all central to New Jersey Attorney General Matt Platkin’s recently filed appeal of the indictment of Norcross et al. that was dismissed by the court.)

It is these tax incentives that are spurring construction in New Jersey, Sweeney told the business publication ROI-nj.com, not the private sector. “I can tell you that construction jobs that have come over the last several years are from incentives and higher ed. It’s all been government-driven, because private sector is not coming here, period.”

When it came to light that a lobbyist who worked for Phil Norcross, George’s brother, actually wrote parts of the law, Sweeney argued to ROI-nj.com that that was just the normal way Trenton operates. “How do you think legislation gets done?”

These lucrative tax breaks generated hundreds of construction jobs along the Camden waterfront. But they did little to provide jobs for Camden residents. Nor did they rebuild more than a few streets of the city. Nor did they mean much new business coming to New Jersey. And when the corruption involved in legislating these tax breaks came to light and the Murphy administration demanded they be radically downsized, Sweeney strongly defended the machine.

The building trades unions know Norcross’s value to them. When Attorney General Matt Platkin indicted Norcross last June for racketeering and running a “criminal enterpris,” (which included a part for Sweeney, as TNJD revealed last week), the state AFL-CIO and the New Jersey Building and Construction Trades Council filed a brief asking the court to dismiss the case. They argued that Norcross’s behavior was just normal business practice in New Jersey.

Over the years Norcross and Sweeney, aided by both the financial largesse of the building trades unions as well as their boots on the ground get-out-the-vote efforts, have elected dozens of county commissioners, city mayors, and town council members who in turn have directed local building projects to their contractor and union allies.

And thanks to a new law two years ago, contractors and unions can grease the wheels for contracts by pouring significant money into county Democratic committees. And they have, as TNJD revealed:

“Contractors, attorneys and labor union PACs contributed $371,350 to the Essex County Democratic Party in 2024. That’s nearly half of its total take of $797,409. And while a small portion of that union money came from teachers (NJEA) and AFSCME (just $8,000 in all), the vast majority of the union money came from a dozen or so construction-related unions.”

The building projects these donations pave the way for can be way out of proportion to what a town actually needs.

Unlike most unions, which see their employers as adversaries, people they have to negotiate with, the building trades unions work closely with their contractor bosses. Their unified goal is winning contracts, and they often see environmental and other regulations as the enemy.

There is a “hand-and-glove partnership” between the building trades unions and their allied contractors in creating and running apprenticeship training programs, according to Bill Mullen, head of the New Jersey Building and Construction Trades Council, who’s endorsed Sweeney. Contractors performing public work are required to participate in an approved apprenticeship program. Both unions and contractors fund the apprenticeship programs, allocating over $100 million in 2022, Mullen wrote.

Construction workers and their business allies also collaborate through Engineers, Labor-Employer Cooperative, (ELEC, not to be confused with New Jersey’s Election Law Enforcement Commission, also called ELEC). ELEC was jumpstarted by the International Union of Operating Engineers Local 825, who operate heavy machinery at construction sites, side by side with contractor executives. “In 2010, the major building contractor associations in New Jersey and New York joined together with IUOE Local 825 to form a collaborative labor-management organization to support their common interests in expanding work opportunities for their memberships,” according to their website. They have pressed for major bridge-building projects, pipeline construction and large-scale urban redevelopment programs.

The group works with chambers of commerce and other business-union partnerships to pass legislation and get supportive regulations. In fact, in 2024 ELEC spent $833,169 lobbying the New Jersey legislature, more than any special interest company or group. The Operating Engineers, who backed Sweeney’s re-election in 2021, when he was beaten by a little know Republican truck driver, dropped out of the New Jersey Building Trades and Construction Council two years ago after a falling out with its head. It now backs Josh Gottheimer in the gubernatorial race.

[This article has been corrected to reflect that the fact that Platkin has recently appealed the dismissal of the indictment of Norcross. He did not file a new indictment.]